|

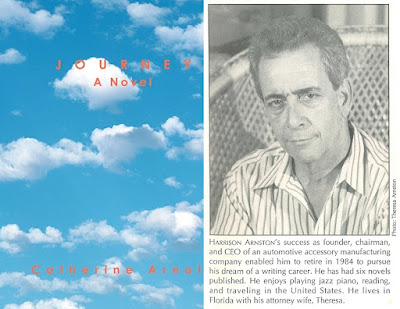

Journey by

Catherine Arnold (Harrison Arnston?)

iUniverse, 2003

In the early-1990s my parents sprang for a subscription to

the bulletin board service Prodigy. Prodigy was a predecessor to

AOL and (ultimately)

to the commercialized internet we have today. Basically, Prodigy was a

bunch of bulletin boards where people with similar interests gathered to chat

about what made them excited. I tended to spend my time—or perhaps misspend

my time—on boards about books and baseball. One of the boards I frequented

was called Harry’s Bar & Grill. Its operator was a thriller writer

named Harrison Arnston. He went by Harry in both the real and digital worlds,

but his novels were published as “Harrison”.

Harry was a renaissance man—cool,

successful, and kind. His board was about writing and he knew what he was

talking about. When I first met Harry—the digital version anyway—he had

published four novels; all paperback originals released by Zebra. In 1984, Harry

had sold his successful California “auto-accessory company,” moved to Palm

Harbor, Florida, and set out to write thrillers. It didn’t come easy, either.

After reading his first thriller, which was never published, one agent told

him to find another hobby. But Harry wrote another and then another before he

found print with Zebra.

Harry was the first “real”

writer that took an interest in me, or at least made me feel like he did, and

I loved every piece of advice he gave me and anyone else that wandered into Harry’s

Bar & Grill. In the early-1990s, HarperPaperbacks became Harry’s

publisher and the quality if his work noticeably improved. Jon L. Breen noted

that Harry’s legal thriller, Act of Passion (1991), was “unusually

well plotted” and every book Harry wrote was better than the last. Harry’s

journey ended prematurely in 1996, he was 59, after a brief battle with lung

cancer, but I’ve always wondered what he would have produced if he hadn’t

died.

My point? I think I found Harrison

Arnston’s final novel. It was self-published by Arnston’s widow, Theresa

Sandford-Arnston, using her pseudonym, Catherine Arnold, with the title, Journey.

Unfortunately, Ms. Arnston died in 2016 and so I can’t ask her. I haven’t

been able to make contact with any of his or her family, either. And I’ve

tried. But after reading Journey—which is a cool take on an X-Files

theme—I’m convinced it was written by Harry Arnston because it is

stylistically similar to his last few published novels. Another clue, and it

is a big one, comes from Harry’s St. Petersburg Times obituary (Feb.

4, 1996) stating his agent was peddling a novel titled Journey.

My only hesitation about Journey

belonging to Harry Arnston is, back in 2008 I exchanged emails—at least three

or four—with Theresa Arnston about Harry and she said his only unpublished

book was a thriller titled American Terrorist. Journey had been

published five years earlier, but I’m puzzled why she wouldn’t have told me

about Journey.

Now, a

little about Journey. It was obviously written in the mid-1990s

because it mentions the first World Trade Center bombing and the Waco siege (both

in 1993), and the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995, but nothing significant

after that. There are a few add-ins, a line here or there that feel like they

were dropped in by another writer and don’t exactly fit the overall context.

One such add-in is a mention of the 2002 film, The Hours. Journey

has that big 1990s thriller feel, too—weighty problems, significant

background detail, lightweight characterization, but still richer than most

current genre thrillers, and a quality of we can do it hopefulness

that we seemed to lose after 9/11.

Everything begins when a 747

disappears from an air traffic controller’s radar screen. There is no

evidence the airliner crashed, changed course, or exploded. It simply

disappeared. The investigation is handed to the FBI, but—against all

protocols—the Pentagon assumes control with the blessing of the Department of

Justice’s top suits. A development that irks the FBI’s top investigator, Jack

Kalman, enough that he takes leave and starts his own investigation.

There is a bunch of detail

about how air traffic control worked in the 1990s, including the

ramifications of when Ronald Reagan broke the union in the 1980s. The action

is swift and—especially the first two-thirds while the happening is a still a

mystery—intriguing. There are several repetitive passages, but none are

overly long, and I bet if this had been published in Arnston’s lifetime they

would have been fixed. A strange prologue—strange because it was obviously written

by another writer—is attached with little relevance to the narrative and

there are a few odd typos in the text. Odd, because it seems like the wrong

word was used. But overall, Journey, is an attractive, high-speed,

flight that would have been even better if it had been published when it Harry

Arnston wrote it.

Click here for the Kindle edition or here for

the paperback at Amazon.

|