|

Booked

(and Printed) July 2024 July always plays better on paper than in the real world.

It is too hot, the days are too damn long, and I never get as much reading

done as I would like. This July was no different than any other. I read a sparse

five books—sparse because two were far short of novel length. The

first of these thin interludes is DIVVY UP: SCIENCE FICTION STORIES, which is a marvelous

collection of three tales—one novelette and two shorts—written by Stephen

Marlowe in the 1950s. Marlowe was best known as a crime writer but he could

write just about anything and he truly excelled at turning out entertaining

science fiction. You can read more about Marlowe and this collection here,

which I should tell you was retitled as Alternatives: Science Fiction

Stories. The other shorty was the mediocre thriller COME AND GET US, by

Shan Serafin, about a family being hunted in the Utah-Arizona desert. Published

in 2016 as part of James Patterson’s BookShots series of novellas, which

was a cool idea that never worked out in either quality or sales, Come and

Get Us lacks plausibility and characterization, but the setting and

action sequences are sharp enough to have kept me turning the pages. Speaking

of short stories—the latest single author collection from Stark House, CREAM OF THE CROP: BEST MYSTERY & SUSPENSE STORIES OF BILL PRONZINI (2024),

is as good a collection as I’ve read this year. It covers Pronzini’s entire

career from the late-1960s to 2023. There are standalones, Nameless detective

tales, and one entry from the historical detectives series, Quincannon &

Carpenter. It is highly recommended and you can read more of my thoughts

about it here. Of the five individual short stories I

read, which were all enjoyable, my favorite was Ed Gorman’s “A DISGRACE TO THE BADGE”—a standalone

western about an alcoholic lawman, a spoiled rich kid, and a locked-room murder—is

rich with characterization and atmosphere and, best of all, it is ironic and

surprising. I’m not sure when “A Disgrace to the Badge” was originally

published since The Long Ride Back (2004), where I read it, had a

disappointing copyright page. The two shorts I read by James Reasoner—“DOWN IN THE VALLEY” (1979), “DEATH AND THE DANCING SHADOWS” (1980)—both fit comfortably in

the crime / detective field. I had read “Down in the Valley” once before and

Reasoner’s ability to shift perspective from one character to another so

easily, and without any confusion for the reader, is amazing. I liked “Death

of the Dancing Shadows” just as well and reviewed it in detail here. |

|

|

|

I dug both full-length novels I read in July. ROBAK’S WITCH, by

Joe L. Hensley (1997)—which is my favorite read of the month—is the eleventh (of

twelve) book in the Don Robak series. Robak is a rural Ohio attorney, soon to

be judge, with experience working death penalty cases. When he is called in to

help an old friend from law school defend a woman accused of murdering her

teenage niece and nephew, Robak finds a community convinced of her guilt. A

wacky fundamentalist church spreading rumors she is a witch and far too many citizens,

including the County Sheriff, content with going along. You can read my review

here. Then, of course, I read the next in David

Housewright’s McKenzie series, CURSE OF THE JADE LILY (2012), because boy do I love

these books. McKenzie is a witty, funny, and likable cuss with several

million dollars in the bank and nothing to do but favors for friends. In this

one, McKenzie helps a museum get a priceless artwork back after it was stolen

by their security chief. The busy opening and sprawling character list mark

this one down from the best in the series, but it is still good fun. The only book I started and chose not to

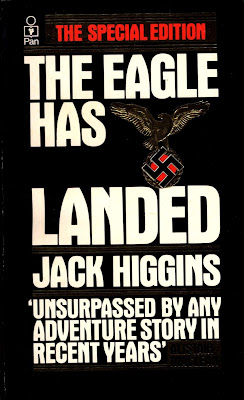

finish was Jack Higgins’s 1992 EYE OF THE STORM, which is where Higgins’s longtime

series-character Sean Dillon was introduced. The Dillon books have never been

my cuppa but I have fond memories of reading Eye of the Storm back

in my innocent youth. While Eye of the Storm still held some

attraction for me, I simply wasn’t in the mood. Maybe I’ll try reading it

again in one of the colder months when I’m not quite as grumpy. Fin— Now on to next month… |

|

|