|

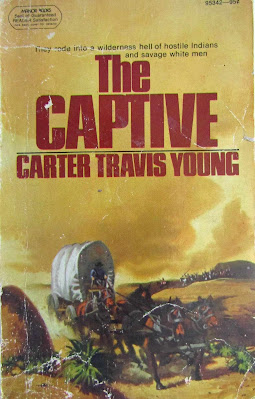

The

Captive

reviewed by Mike Baker Louis Charbonneau wrote one of my favorite action novels Night

of Violence (aka The Trapped Ones) about a motel and its occupants

trapped with a desperate criminal fleeing his boss’s wrath and the two hard

cases sent to kill him. I cannot sing this book’s praises enough. It’s a slim

taut thriller. Most people know Charbonneau

for his science fiction, which I’m sure is great but I wouldn’t know because

I don’t read science fiction. I found out though, in early April, that he

also wrote westerns under the pseudonym Carter Travis Young. I immediately

bought five of them. The Captive is

about freshly married Ter and Jaine Bryant as they optimistically sojourn

west from Natchez, Louisiana on their way to recently opened California.

Their wagon train stops at Bent’s Fort where they lose their escort of

Dragoons and shortly thereafter, Jaine is kidnapped when their train gets

attacked by the Iron Nose band of Comanches somewhere out on the trail. Ter teams up with the father

of another white girl stolen by the Comanches and Tom Brock, a black scout

Ter befriended on the wagon train, and the trio head out to get their kin or

get their vengeance. Jaine gets raped a lot and then stolen by a

Cheyenne and raped some more. Meanwhile, mountain man Angus

Haws loses his Apache squaw Wo-man to a bear attack and, having seen the

ethereal Jaine Bryant at Bent’s Fort, obsesses about her as he wanders into

the wilderness pining for a white woman of his very own. Shenanigans ensue. The first act is in real time

up through the abduction. The second act is a Rocky style montage of events

over the course of about a year: Ter and Tom became a scout team for the

Cavalry, Angus buys Jaine from the Cheyenne who murdered Iron Nose and Jaine

gets raped some more. The third act is in real time as Tom and Ter close in

on the increasingly more insane Angus and the beleaguered and aggrieved

Jaine. The writing is crisp and the

suspense, where the story calls for suspense, is tight. The rapes are low key

if there’s such a thing as a low-key rape and there’s a lot of them. The

gun-play and violence is sparce but explosive and effective. |

|

The Captive was originally published as a hardcover in 1973 by Doubleday

& Co. The edition our intrepid reviewer, Mike Baker, read was the mass

market edition published by Manor Books. Come back the first Monday of each month

for Mike Baker’s latest journey into 20th Century paperback fiction.

|